Abilities, Domains, and the Transdisciplinary Mindset

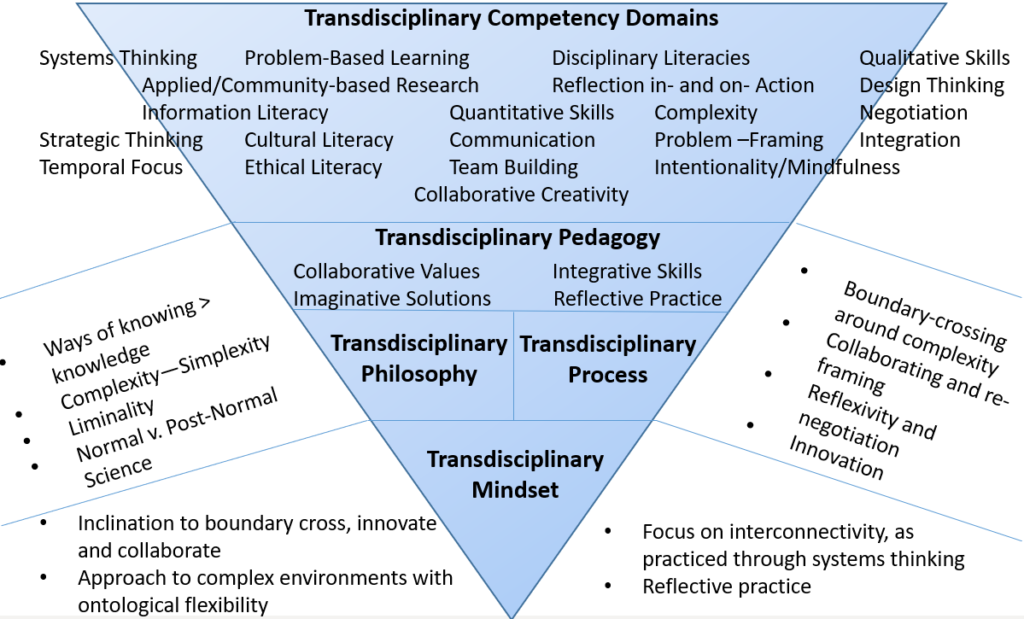

The Transdisciplinary Studies Program, in conjunction with our transdisciplinary studies colleagues at other research institutes and universities, has identified the following abilities and domains as critical components in fostering a transdisciplinary mindset.

Abilities

- Communicating Values: transdisciplinarians are able to identify, ground, and communicate assumptions and normative values in topics related to the problem(s) under consideration.

- Reflective Practices: transdisciplinarians are reflective about their own perceptions and biases concerning disciplinary concept(s).

- Effective Collaboration: given a real-world topic and its accompanying conflicts and uncertainties, transdisciplinarians are able to identify and frame clear, relevant problems with others who have contrasting perspectives or opinions.

- Integrative Skills: transdisciplinarians are able to translate real-world problems into viable research questions, to identify and integrate adequate research method(s) and to apply conceptual knowledge to specific contexts to investigate these questions and to co-produce knowledge with society.

- Imaginative Solutions: transdisciplinarians are able to explore and develop solutions for real-world problems, while being aware of the possibility of unintended consequences of these solutions and taking responsibility for these consequences.

Competency Domains

Each of these abilities is further grounded, in part or full, in the following competency domains, which embody the transdisciplinary mindset through both research and practice.

Thinking Styles

Systems Thinking: “an enterprise aimed at seeing how things are connected to each other within some notion of a whole entity.” In other words, it is a “way of looking at phenomena and problems through a holistic lens, including how components of a given systems affect one another as well as affect the system as a whole.”

Design Thinking: A cyclical process in which a team defines a goal, designs a prototype, tests the prototype, and reiterates this until the goal is achieved. Design-thinking focuses on the intention of an intervention or product (and evaluating its success), in contrast to finding a universal truth or theory.

Strategic Thinking (from ‘strategic management’): In an organizational setting, this refers to the generation and application of effective plans that are in line with the organization’s objectives in order to create a competitive advantage. In strategic thinking, an effective strategy is divided into 1) process, 2) content and 3) context. At the heart of strategic thinking is creativity and inventiveness.

Temporal Focus: The degree to which individuals think about the cognitive constructs of past and future (and their fields of study) and how these relate to the present, as well as how the study of chronological concepts can be applied to other fields.

Intentionality/Mindfulness: In contrast to causal frameworks, a set of perspectives focusing on agency, meaning-making, wisdom, and a moment-by-moment awareness of both thoughts and feelings as valid ‘ways of knowing’.

Problem-Based Learning: A constructivist pedagogy based on student collaboration around open-ended, complex questions to develop skills for use in future practice. It is an active learning set of techniques that drive both the process and the motivation for learning.

Literacies

Information Literacy: The ability to define problems in terms of information needs and apply a systematic approach to locate, evaluate, and apply the given information. Critical thinking is applied to evidence, and so users of this literacy are capable of not only telling ‘fact from fiction’ but also understand how information can be curated according to intention.

Cultural Literacy: The ability to understand and participate fluently in communication through cultural products and artefacts, emphasizing narrative, rhetoric, comparison, interpretation and critique for the learner to better understand and utilize cultural and disciplinary contexts.

Ethical Literacy: The ability to reflect on, articulate, and respond to issues concerning morality and ethics across relativist to essentialist perspectives. This type of literacy combines the ethical and value-dimensions of a profession/field/group with policy knowledge and technical skill.

Disciplinary and Topic Literacy: An understanding of the knowledge base, lexicon, and skills used in a given discipline. Objectives in this category of literacies is to be able to process and create literature that contributes to the conversations/debates particular to a specific discipline or topic.

Effective Collaboration Skills

Negotiation: a “form of social interaction that incorporates argumentation, persuasion, and information exchange into reaching agreements and working out future interdependence.” In a collaboration, this pertains to interest-based negotiation in which the relationship is treated as a valuable element of what is at stake, while seeking an equitable agreement.

Communication: in collaboration (and conflict resolution) this refers to constructive, positive communication (eg. active listening, giving feedback, using respectful language) as well as finding or creating a common language for shared understanding across boundaries. It also emphasizes choosing effective tools, techniques and modalities appropriate for the task(s) at hand, the stakeholders, and conditions dictated by context.

Team building and teamwork: one of the pillars of organizational development based on improving the effectiveness of a team, this specifically refers to aligning members around goals, developing working relationships, and improving communication and trust.

Leadership and followership: Understanding the balance in hierarchical as well as heterarchical organizational structures, as well as the sets of skills required in leaders and followers, specifically in boundary-crossing contexts.

Collaborative Creativity: innovation and emergence in collaborative settings and finding ways to facilitate this type of collaboration. This often describes an approach within collaborative problem-solving that emphasizes idea generation and selection rather than implementation.

Integration of Methods and Perspectives: integration of multiple disciplines in collaborations around complex problems. Integration can emphasize a cognitive, structural, or cultural process. Important questions include what factors are necessary, sufficient and permissive for integration at different levels to occur.

Scholarship

Applied/Community-based Research: research which equitably involves community members, organizational representatives, and researchers in all aspects of the research process. This research often focuses on including community participation, resulting in better understanding of situated problems and empowering citizens to take more control within their communities.

Reflection in- and on- Action: reflection in-action is an awareness of the situation as it happens, and includes the agility, empathy, and self-awareness of one’s own assumptions and biases to change tactics if necessary. Reflection on action is a reflection after a situation has occurred, and a working towards understanding and improving in the future.

Transdisciplinary Case-Study: a specific type of case study focusing on unstructured, complex, large-scale, real-world issues, often including methods for modeling, forecasting, strategy building, and project management. These cases connect academic to non-academic spaces and actors which are go producers of knowledge in the case-study.

Quantitative/Analytical Skills: the ability to visualize, articulate, and solve problems based on available quantitative information. Quantitative methodologies emphasize objective measurements, statistical data, and computational techniques. Often this is “hypothesis-testing” research.

Qualitative Skills: subjective, observable, but not experimentally measured or examined skills, including critical thinking, creativity, resilience, etc. Qualitative methods emphasize the values in an inquiry and how meaning is made. Often this is “hypothesis-generating” research.

Complexity Theory: based in systems theory and used in organizational settings, used to discuss complex systems; their adaptability, dynamicism, and resilience. It is the study of how order, patterns and structure appear in complex adaptive systems, and it focuses on emergent phenomena over deductive and inductive reasoning.

Problem Framing/Hypothesis (re-)Generating: when collaboratively working through complex systems, an iterative process used to reframe a problem from various perspectives, both to help understand its complexity as well as to solve it. It comes from a synthesis from conflict resolution and the cognitive sciences.

Again, these core abilities and competency domains embody transdisciplinarity through both research and practice. These are the “things” that transdisciplinarians should do to develop a transdisciplinary mindset because the great ideas and solutions to complex, wicked, real world problems are crafted by teams, are never “done,” and are what matters in driving our world forward.1

1Alan J. Perlis, “The Computer in the University,” Management and the Computer of the Future, ed. Martin Greenberger, MIT Press and John Wiley.

Share